The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local Union 160 was chartered on June 25, 1935, in the Twin Cities, Minnesota.

Born during the tumultuous labor environment of the Great Depression, the union emerged the same year as the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act) was signed into law, creating a new framework for labor rights in America. From humble beginnings with just 13 founding members from Northern States Power Company, Local 160 grew to become a powerful voice for electrical workers throughout Minnesota. This history chronicles the challenges, struggles, and triumphs of a union that fought against strong anti-labor sentiment to establish fair working conditions and representation for its members.

The Birth of IBEW Local 160

(1933-1935)

A Hostile Environment for Labor

In the wake of World War I, Minneapolis had earned a reputation as an "open shop" town among employers and was widely known to laborers as "one of the worst scab cities in the country." This anti-union environment was carefully maintained by powerful business interests, particularly the Citizens Alliance—a group composed of major business executives from the Minneapolis area—and the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce.

These organizations developed what was considered the most complete system of anti-union machinery in the country. They successfully infiltrated unions with agents and labor detectives, crushing most major strikes in the Twin Cities through the 1940s. Additionally, Minneapolis labor had traditionally been cheap and plentiful, drawn from the state's wheat fields, allowing employers to maintain low wages and poor working conditions.

The Political Landscape Changes

The labor movement found allies in the Wobblies (Industrial Workers of the World) and later the Farmers-Labor Party, which formed in 1918. By 1930, the Farmers-Labor Association had succeeded in placing many of its members in public office, including Governor Floyd B. Olson, who advocated for social change and workers' rights.

The onset of the Great Depression created desperate conditions in Minneapolis. By January 1931, 35,000 men were unemployed in the area, and by the winter of 1931-1932, both state and local relief funds were nearly depleted. President Roosevelt's "New Deal" and the National Recovery Act (NRA) of 1933 began to provide relief and established new rights for workers, including the right to organize and bargain collectively.

The Truckers Strike of 1934

The spring of 1934 saw Minneapolis truckers launch a strike that effectively shut down economic activities in the city. Led by the Dunne brothers, Farrell Dobbs, and Karl Skoglund, the strikers developed innovative tactics that would later be used in labor strikes throughout the country. Despite fierce opposition from the Citizens Alliance and bloodshed during the conflict, the truckers ultimately prevailed in August 1934, establishing wage and hour standards, grievance machinery, and explicit recognition of the right to bargain collectively.

Thirteen Men Take a Stand

It was against this backdrop that 13 men from the Trouble and Overhead Departments of Northern States Power Company (NSP) took the first steps toward forming what would become IBEW Local 160. Frustrated by a $10 monthly pay cut and seeking a voice in their wages and working conditions, these men initially approached IBEW Local 292 for representation.

When Local 292's efforts to address their grievances through a city-wide labor review board proved ineffective, the men decided to form their own union. By June 1934, they had started a membership drive and applied for a charter with the IBEW under the title Local Union 160. By July, they had elected officials and were holding regular bi-monthly meetings.

With guidance from International Vice-President Mike Boyle and support from Local 292 members who worked for NSP, the fledgling union grew stronger. On June 25, 1935, Local Union 160 was officially chartered as a member of the IBEW, marking the formal beginning of an organization that would fight for electrical workers' rights across Minnesota for decades to come.

Early Struggles and Growth

(1935-1937)

Building Membership and Solidarity

Following their charter in June 1935, Local 160 faced the immediate challenge of building a strong membership base. Though they had gained official recognition, the union initially had only sixteen accredited members in their ranks. The Executive Board, which was also given authority as the Organization Committee, recognized the need for an official organizer and selected one from Duluth. When this approach yielded poor results, they switched to a door-to-door committee strategy to inform and recruit NSP employees.

To ease the financial burden on new members, the union restructured its payment system. While dues remained at $3.00 per month with a $7.00 initiation fee, members could now pay the initiation fee at the rate of $1.00 per month over seven months. This change helped increase membership, providing the union with greater legitimacy in the eyes of the International Office and more funds to support its activities.

Brotherhood Beyond the Workplace

Local 160 quickly understood the importance of solidarity with other unions. The local became active and sympathetic to all strikes and organizing efforts in the area, often providing financial support by attending fundraising dances or picnics held by other locals. These activities strengthened the brotherhood of the union movement as a whole.

Within their own ranks, Local 160 fostered fraternal feelings by sending flowers to all members who were ill, reinforcing the sense that everyone belonged to a supportive community. This brotherhood approach not only improved morale but added to the union's strength and unity.

Negotiations and the First Strike

The first labor agreement negotiations with NSP began in late 1934. The union received valuable advice from Farrell Dobbs, Secretary-Treasurer of Teamsters Local 574, who taught them to aim high in their initial proposals to ensure favorable compromises. Despite his skills as a negotiator, NSP President Pack refused to negotiate if Dobbs was present, insisting on dealing only with IBEW representatives.

By 1936, negotiations had stalled, with the company proposing wage decreases and ineffective grievance procedures. On June 30, 1936, the Underground and Overhead Departments voted to strike with the union's backing. When the company still refused to negotiate, the remaining departments joined the picket lines on July 1. The strategy worked—by July 15, NSP President Pack had signed an agreement acceptable to the union.

The First Business Agent and Expanding Reach

In July 1936, Henry Shultz was appointed as the union's first Business Agent, despite not being a union member or NSP employee. Shultz and his assistant Heigel worked to organize branch locals in St. Cloud and St. Croix Falls, expanding the union's power and effectiveness. These branch locals would abide by Local 160's decisions, meaning that any future company-wide strike would affect more than just the Minneapolis Division.

The 1937 Strike and Amalgamation

By February 1937, negotiations with NSP had again reached a standstill. On the suggestion of International Vice-President Mike Boyle, the union decided to amalgamate with Minneapolis Local 292 on March 1, 1937, and subsequently called a company-wide strike. The eight-day strike proved effective, resulting in a landmark agreement that included:

- Representation for 3,000 employees (despite only 26 of NSP's 5,000 employees belonging to the union).

- Restoration of wages to pre-depression levels

- Clear explanation of seniority rights and working conditions.

- Payment for all eight days that workers were on strike.

The International Office played a crucial role by convincing NSP to bargain with only one union, preventing potential jurisdictional disputes within the company in the future.

Establishing a Foothold

(1938-1939)

Rechartering and Renewed Independence

On August 30, 1938, after a period of amalgamation with Local 292, the union was rechartered by the IBEW as Local Union B-160. This marked a return to independence and was followed by the election of new Executive Board members and a Business Manager/Financial Secretary. The Business Manager position carried significant responsibility, including organizing and informing the membership about financial matters, as well as controlling union expenditures and receipts.

Strengthening the Union Structure

A major addition to Local 160's structure during this period was the Seniority Board. This board was empowered to assign seniority dates or company starting dates for union members, which were critical for promotions, lay-offs, and eventually pension assignments. By transferring responsibility for seniority lists from the company to the union, Local 160 gained greater control over an important aspect of members' employment security.

The union also established a more formal system of Union Stewards. These representatives were either elected or appointed from the membership and needed a thorough understanding of the working agreement and a willingness to help others. Stewards served as agents of the union in constant contact with workplace situations governed by the labor agreement.

Resolving Jurisdictional Disputes

During this period, Local 160 had to address frequent jurisdictional disputes—conflicts over which trades or industries had the right to perform specific duties. Most of these disputes involved other IBEW locals and determining which local had the right to assign its members to specific jobs. Through negotiation and agreement, Local 160 secured jurisdiction over all work performed on NSP properties, an important victory for the union's authority and stability.

Continued Challenges with NSP

The relationship with NSP remained contentious. In October 1938, President Pack sent a letter to all locals representing NSP employees, canceling all agreements. This was widely seen as an attempt to slow unionization at the company and potentially end the union movement in the Minneapolis area. The company also employed stalling tactics during negotiations, including making its Director of Labor Relations, Mr. Miller, unavailable for meetings or unwilling to stand by previous agreements.

Despite these challenges, Local 160 persisted in its efforts to secure a new agreement before the 1938 contract expired. The union's determination and growing strength eventually forced the company to engage more seriously in negotiations.

Remarkable Growth

By 1939, Local Union 160 had grown from the original group of 13 men to a strong and influential membership of 1,076. The union's reach had expanded from two departments to cover workers in four divisions across Minnesota. With this robust membership and a vision for the future, IBEW Local 160 had established itself as a significant force in Minneapolis labor relations and throughout the state.

The Fight for the Union Shop

(1948)

The Impact of the Taft-Hartley Act

In January 1948, Local Union B-160 took steps toward securing a "Union Shop" agreement—something the local had advocated since their 1940 contract negotiations with Northern States Power Company. This initiative came in response to the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which modified the rules for union security arrangements.

Under Section 8(a)(3) of the Act, employers could make agreements requiring union membership as a condition of employment after the thirtieth day following the beginning of employment or the effective date of the agreement, whichever came later. However, the Act's definition of "union shop" differed from the traditional definition—under Taft-Hartley, unions could only have a worker discharged for non-payment of dues and initiation fees, not for other reasons for expulsion from the union.

Navigating the NLRB Requirements

To secure a union shop agreement, Local B-160 needed to comply with complex requirements. The union had to:

File a petition with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) for Authority for Bargaining Relative to Union Security.

Obtain authorization signatures from at least 30% of the membership in the NSP bargaining unit.

Submit NLRB forms 1080 and 1085, listing union officials and certifying that financial information was available to members.

File a Labor Organization Registration form with the Department of Labor, detailing officers, bylaws, finances, and dues.

Submit affidavits confirming that union officials were not members of the Communist Party or any organization advocating overthrow of the U.S. government.

The Executive Board took action on January 27, 1948, deciding to apply for a petition for an authorization election on the Union Shop issues. Authorization cards were printed and mailed to members to obtain the required signatures.

The Foremen Inclusion Dispute

While preparing for the election, a dispute arose with NSP regarding the inclusion of foremen in the bargaining unit. The company contended that foremen were supervisors under Section 2(11) of the Act because they controlled work duties and had disciplinary authority. The union, citing previous agreements that included foremen in the bargaining unit, fought to maintain this arrangement.

The dispute was resolved on March 15, 1948, when NLRB Attorney Erwin Peterson ruled in favor of the union, deciding that foremen should be included in the bargaining unit in the NSP contract. This decision led to the signing of an Agreement for Consent Election by Frank J. Gleason, Director of Personnel at NSP, and Harry E. Leonard, Business Manager at Local Union B-160.

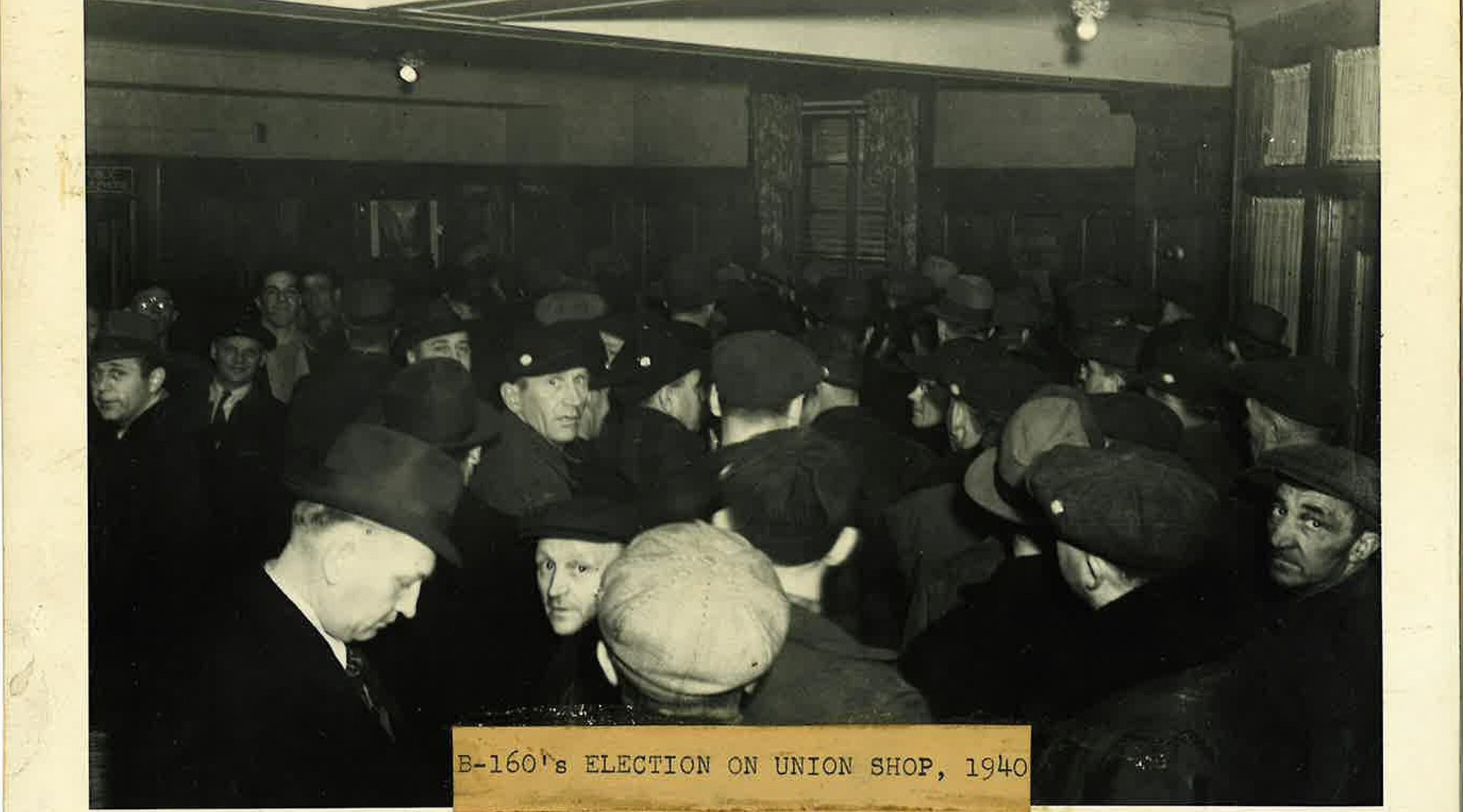

A Historic Election

The Union Shop election was scheduled for April 15, 1948, at the NSP warehouse on 16th and Chestnut in Minneapolis. Between April 1st and April 15th, the union campaigned vigorously for passage of the Union Shop Petition, stressing that not voting would be considered a vote against the union, as a majority of eligible voters was needed for approval.

The election results were overwhelming: of 1,081 eligible voters, 1,021 cast ballots. After accounting for challenged and void votes, 927 members—86% of eligible voters and 94% of those voting—supported the Union Shop Agreement. This resounding endorsement demonstrated the membership's commitment to union representation and set a precedent for all future organizational and negotiating activities of Local B-160.

From Humble Beginnings to Powerful Representation

The growth of IBEW Local 160 from its modest origin of 13 determined workers to a membership exceeding 1,000 by 1939 represents one of the most remarkable success stories in Minnesota labor history. This expansion wasn't merely numerical—it represented a fundamental shift in power dynamics between workers and management at Northern States Power Company and throughout the electrical industry in Minnesota.

Establishing Industry Standards

Through persistent negotiation and strategic action, Local 160 succeeded in establishing critical workplace standards that many take for granted today:

Restoration of wages to pre-depression levels

Clear seniority rights and protections

Effective grievance procedures

Improved safety conditions

Job security provisions

Fair overtime compensation

These achievements not only benefited union members but helped set standards for the entire electrical industry in the region, improving working conditions for countless workers beyond the union's membership.

Building Labor Solidarity

From its earliest days, Local 160 recognized the importance of solidarity with other unions and labor organizations. By actively supporting other strikes, participating in broader labor initiatives, and maintaining strong connections with organizations like the Central Labor Union of Minneapolis and Teamsters Local 574, the union helped strengthen the entire labor movement in Minnesota.

The union's success in securing the Union Shop agreement in 1948 further solidified its position and created a model for other unions to follow. By 1982, 60% of the union's contracts operated under Union Shop provisions, with the remaining 40% functioning as either Open Shop or Maintenance of Membership arrangements.

A Continuing Tradition

The story of IBEW Local 160 is more than a historical account—it's a living legacy that continues to shape labor relations in Minnesota's electrical industry. The principles of solidarity, determination, and strategic action established by those first 13 members and expanded upon by generations of union leadership have created an enduring institution that continues to fight for fair treatment, safe working conditions, and economic security for electrical workers throughout the state.

The union's history demonstrates that significant change is possible even in the most hostile environments when workers stand together with conviction and purpose. This legacy of courage and persistence remains at the heart of IBEW Local 160's identity as it continues to represent electrical workers in an ever-changing industry.

Explore the Archives

Elected Leaders

Business ManagersOfficers

Executive Board

Union Hall Staff

Business RepresentativesOffice Staff